The Kids Aren't Alright

Platforms profit from children. Parents profit from platforms.

Snapchat’s stock just tanked. A new class-action lawsuit claims executives misled investors about user growth and competitive threats from Instagram — wiping billions off the market cap overnight.

Investors are furious.

But not about Snapchat’s product design.

Not about youth-targeted features exploited by predators.

Not about the millions of children under 18 — many under 12 — hooked on systems designed for behavioral addiction.

They’re furious about missed earnings.

Meanwhile, Instagram just rolled out Instagram Map — a Snap Map clone embedded directly into DMs and location-tagged content. The feature lets users share their real-time location with friends and explore posts tied to specific places.

Meta pitches it as connection. Lawmakers are already calling it dangerous.

⸻

Instagram Map: Meta’s Competitive Escalation

Snap Map debuted in 2017 with the same promise of intimacy and discovery — and quickly became a magnet for stalking, grooming, and harassment. Snapchat anticipated risks but underestimated the volume and speed of abuse once millions of teens enabled location-sharing.

Meta has no such excuse.

By the time Instagram cloned Snapchat’s riskiest feature, Meta had years of data showing exactly where this road leads:

- Snap Map’s stalking scandals and exploitation reports

- Law enforcement warnings about grooming risks

- Internal Meta research on predators using DMs and algorithmic clustering

- Lawsuits and congressional hearings documenting youth harm

And yet Instagram Map launched anyway.

Because location drives intimacy, intimacy drives engagement, and engagement drives growth.

Instagram’s pitch:

- Share live location with select friends

- Discover hotspots based on where others are posting

- Integrate seamlessly into DMs, Reposts, and the Friends tab

It sounds harmless until you see the pattern:

Youth-targeted by design — location-sharing disproportionately appeals to teens and younger users, who treat it as social currency.

Opt-in, but performative — by embedding it directly in private channels, Instagram makes “opting in” feel like participating in friendship itself.

Known exploitation vectors — Snap Map’s history proves how quickly predators exploit location features at scale.

Lawmakers are alarmed — prominent senators are already calling for Instagram Map’s removal, citing youth safety risks.

This isn’t Meta being naïve. It’s Meta weaponizing what it knows about its youngest users to drive growth — even if it normalizes exposure and risk.

Billions lost in shareholder value → lawsuits filed. Millions of children exposed → silence.

⸻

Snapchat’s Experience vs. Meta’s Strategy

When Snap Map launched, Snapchat anticipated risks but underestimated how quickly harm would scale. It built on youth intimacy as an engagement driver and scrambled to contain fallout when stalking and exploitation surged.

I know former Snapchat executives who forbid their own children from using Snapchat. The people who built these features understood exactly how easily they could be exploited — and still, the company shipped first and scrambled later.

Meta didn’t just see the fallout — it studied it.

Instagram Map isn’t innovation; it’s escalation. Meta knows how location-sharing features are abused, knows disappearing DMs and algorithmic clustering create predator pathways, and knows youth adoption will make Instagram Map a hit — and a risk.

Meta knows and doubles down.

This isn’t ignorance. This is deliberate competitive behavior, built on the certainty that shareholders — institutional and individual — will reward growth faster than regulators can act.

⸻

Know Your Customer

In banking, KYC — know your customer — is designed to prevent harm: stop fraud, block laundering, detect risk.

Social platforms also know their customers.

They know kids drive engagement.

They know children under 13 are on their platforms.

They know predators exploit location, DMs, and discovery features.

They know “safety” slows growth.

But unlike banks, platforms aren’t required to act on risk.

They act on opportunity.

And investors — institutional and individual — reward them for it.

⸻

The Foundation: Children

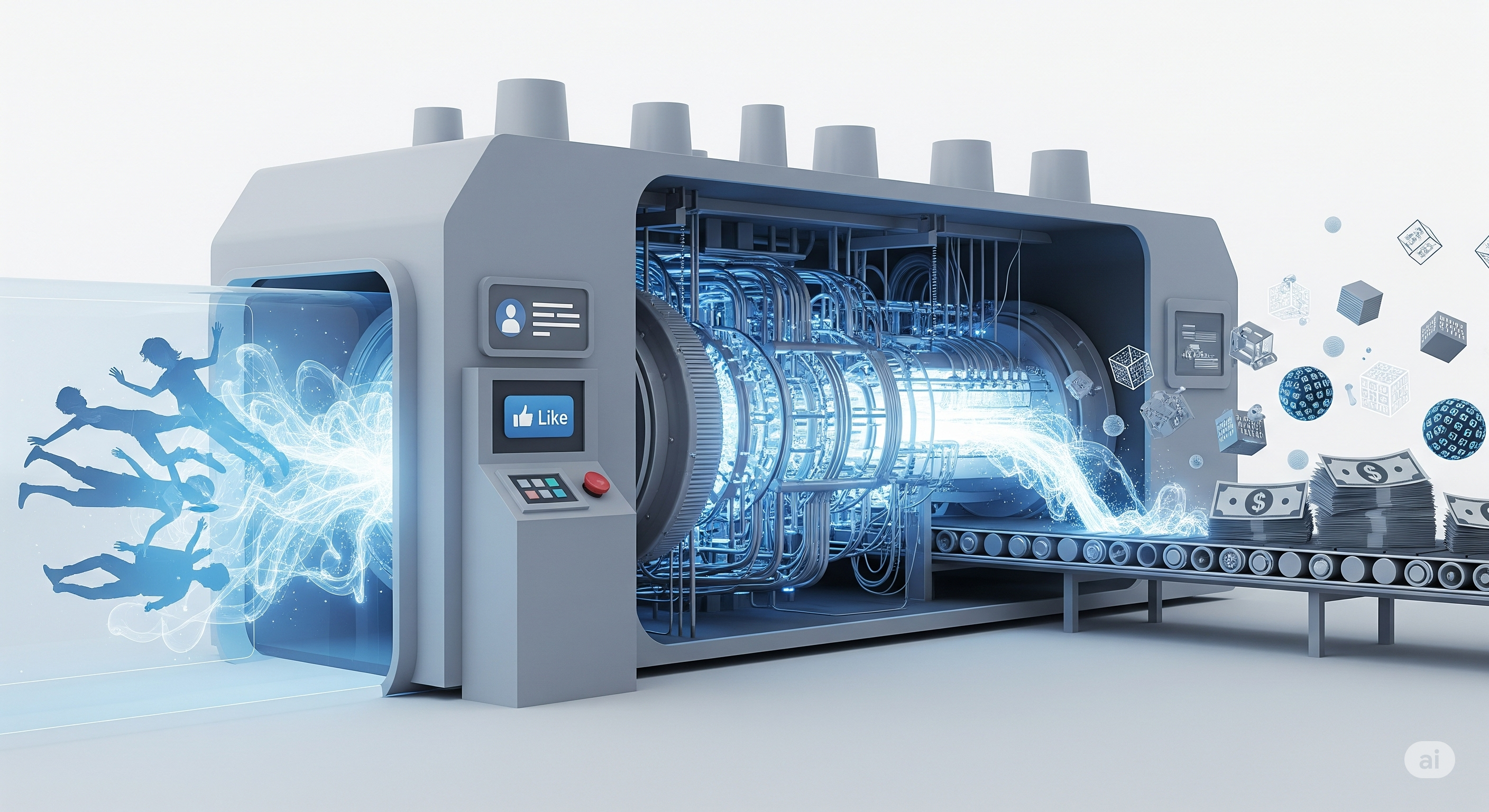

This isn’t a bug of social platforms. It’s the business model:

- Over 40% of Instagram users are under 22

- 1 in 3 are under 18

- An estimated 10–15% are under 12 — below Instagram’s stated minimum

They build features like Instagram Map because youth engagement drives growth:

- Hook kids early

- Normalize exposure and participation

- Profile their behaviors deeply

- Monetize intimacy

The same mechanics that make Instagram addictive also make it dangerous:

Location-sharing → normalized visibility, heightened stalking risk

Disappearing DMs → no audit trail, no accountability

Frictionless discovery → predators connect instantly

Algorithmic clustering → offenders find each other automatically

Grooming isn’t the business model.

It’s simply the cost of doing business.

⸻

The Shield That Shouldn’t Exist

Section 230, passed in 1996, shields platforms from liability for user-generated content. That made sense when platforms hosted content and users found it manually.

Instagram isn’t hosting content. It’s a behavioral prediction engine.

Algorithms decide what you see, who you connect with, and how long you stay. When hashtags guide predators to minors, when DMs enable grooming, when “suggested follows” cluster offenders around victims — these aren’t glitches.

They’re design outcomes.

And Section 230 still treats Meta like a neutral bulletin board.

The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) was passed in 1998, built on a fiction: that children under 13 could be effectively excluded or meaningfully protected online.

In reality:

- Platforms knowingly onboard under-13 users

- Enforcement is rare and fines are trivial compared to revenue

- Algorithms continue profiling minors even when they’re flagged

COPPA lets platforms publicly deny the very user base their growth models depend on while quietly designing products around them.

Together, Section 230 and COPPA enable platforms to ignore known safety risks, ship risky features faster, and treat lawsuits, hearings, and fines as operating costs.

Snapchat shipped first and scrambled later.

Meta studied first and shipped anyway.

⸻

Capital > Children

The hierarchy is brutally simple:

Institutional investors punish missed earnings harder than systemic youth exploitation.

Individual shareholders — parents, traders, pension funds — react to stock price drops, not harm baked into the growth model.

Platforms optimize for engagement because capital markets price it in and reward it every quarter.

The Snapchat lawsuit is a perfect case study: investors who likely have children using these platforms are furious about being misled about competitive threats and user metrics. But those same competitive threats and user metrics depend on hooking children with features that create documented safety risks.

Where’s the lawsuit about that?

Where’s the shareholder revolt about predator pathways?

Where’s the fiduciary duty to the actual humans — many of them minors — whose behavioral data generates the revenue streams being protected?

⸻

The Bottom Line

Instagram Map isn’t just another feature. It’s proof of a system working exactly as designed.

Social media isn’t broken.

It’s working exactly as intended.

Section 230 shields it.

COPPA pretends it’s not happening.

And investors — many of them parents — sustain the cycle by rewarding growth over safety, quarter after quarter.