Chrome’s Future Isn’t for Sale — If It Were, It Should Belong to Everyone

Last week, Perplexity claimed it wanted to buy Google Chrome for $34.5 billion.

It made for easy headlines — but it wasn’t real. Google isn’t selling Chrome. No process. No talks. Not on the table.

And even if it were, the problem isn’t just price. It’s that no plausible buyer could acquire Chrome without triggering massive regulatory backlash, especially in Europe.

Why No Buyer Clears the Bar

Run the list and you hit a wall every time:

- Big Tech rivals like Apple, Microsoft, Meta, or Amazon? Dead on arrival with U.S. antitrust and impossible under EU competition law.

- Private equity? Misaligned incentives, cost-cutting pressure, and profit-driven governance that undermines openness.

- Foreign buyers? Geopolitical firestorm, data sovereignty concerns, and CFIUS roadblocks.

- Telecom/ISP consortia? Net neutrality conflicts and incentive to gatekeep.

This isn’t a product swap. Chrome is core internet infrastructure — a browser with majority market share, a development platform via Chromium, and the default on billions of devices.

Which is why the only realistic path isn’t to sell it to anyone — it’s to put it under shared stewardship.

Precedent Exists

The internet itself was born from public investment — DARPA funded ARPANET, NSF supported core protocols, and that backbone became the global network we all use.

The Linux kernel, which powers Android, AWS, and countless devices, thrives under a foundation model with corporate and government contributions.

GPS, indispensable to global commerce, is run as a free public service funded by the U.S. Department of Defense — but used globally.

Internationally, the concept isn’t radical:

- The BBC operates as a publicly funded broadcaster in the UK.

- CERN advances scientific research through multinational funding.

- South Korea treats high-speed broadband as national infrastructure, backed by direct government investment.

We’ve done this before. We do it now. The precedent is clear.

Anticipating the Objections

“No government will fund a global browser alone.”

True — which is why the model must be multinational. The U.S., EU, and other major economies could co-fund Chrome stewardship, much like the International Space Station or CERN.

“Public stewardship will slow innovation.”

Chrome’s value isn’t bleeding-edge features. It’s stability, security, and universal compatibility. Nonprofit stewardship works — Mozilla has kept Firefox competitive for decades. And a foundation isn’t bound to quarterly earnings, allowing long-term investment in security and accessibility.

“Governance will be a mess.”

We already have functioning models: The Linux Foundation, W3C, and Apache Software Foundation manage large-scale, global, open-source projects with mixed public/private governance. A Chrome foundation could follow the same path, with seats for developers, corporate stakeholders, public interest groups, and multiple national representatives — ensuring no single country controls the project.

The Economics Are Manageable

Google spends an estimated $1–2 billion annually maintaining and improving Chrome.

For perspective:

- The U.S. spends more than that on highway maintenance every few days.

- The EU allocates €95 billion over seven years to research through Horizon Europe.

Funding could come from:

- Direct government appropriations from multiple nations.

- A small levy on digital advertising revenue.

- Contributions from companies that rely on Chromium (Microsoft, Samsung, Amazon).

This investment would secure browser independence for billions of users worldwide while maintaining the Chromium ecosystem that powers 70% of the web.

Regulatory Fit

“Remedies must restore competitive markets, not just reshuffle market power.”

— Jonathan Kanter, DOJ Antitrust Division Chief

EU regulators have been explicit: Dominant platforms cannot simply be transferred to other dominant players. The Digital Markets Act envisions structural separation and infrastructure independence — exactly what a multinational public Chrome foundation would achieve.

A truly open-source Chrome, stewarded by an independent, multinational foundation, is the cleanest antitrust remedy available. It removes monopoly control without creating another one.

The Path Forward

- Convene a working group with the DOJ, EU competition authorities, major Chrome-dependent companies, and open-source foundations.

- Draft a governance charter modeled on the Linux Foundation, with transparent decision-making, multinational representation, and public oversight.

- Secure funding commitments from multiple governments and industry stakeholders before any divestiture process begins.

This framework could be operational over a multi-year transition, with governance and funding agreements in place well before any transfer.

Why It Matters

The Perplexity “offer” was theater. But it points to a serious question:

What happens when essential digital infrastructure is controlled by a single company?

The answer isn’t finding a different owner.

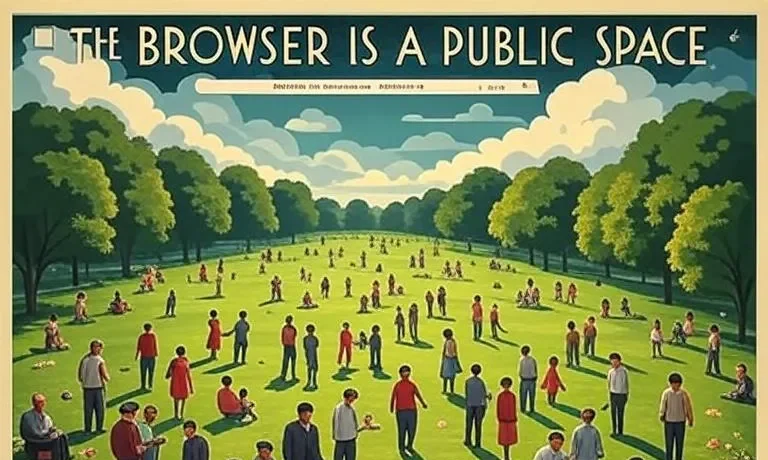

It’s recognizing that some things are too important for any one entity — or any one country — to own.

If Chrome were ever for sale, it should belong to everyone.